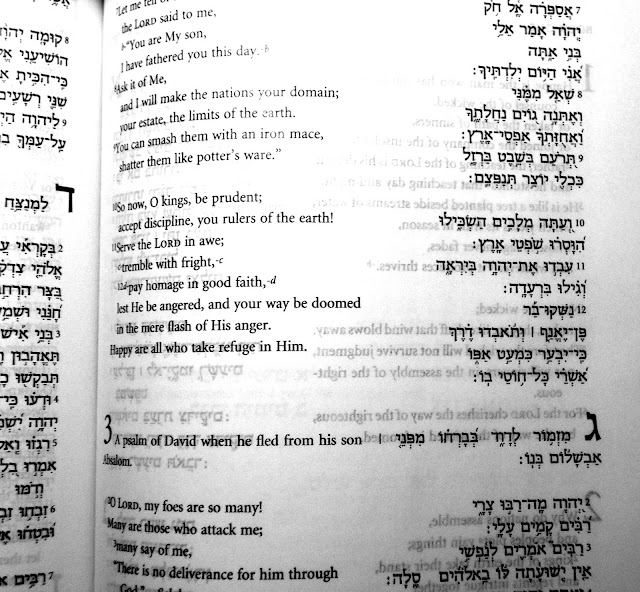

One would not think that the Book of Psalms (Tehillim), some of the oldest poetry that we have, could be a source of controversy, but apparently it can. A single verse can cause contention. In this case the sticking point is the twelfth verse of the second Psalm. The problem is that many Christians believe the verse includes a prefiguring of Jesus, as the Son, while Jews see no mention of a son in the verse. Who is right? Let's try to sort it out.

The mention of a "son" appeared first in the King James Version (KJV) of 1611:

"Kiss the Son, lest he be angry. . . "

What readings were current before that? The oldest we have would be the Septuagint (LXX), the translation made in about 250 BCE by Jewish scholars for the Jewish community of Alexandria:

"Seize upon instruction (draksasthe paideias) lest the Lord should be angry. . . "

In the late fourth century CE, Saint Jerome offered two translations of the Psalms to Pope Damasus for eventual inclusion in what would become known as the Vulgate: one based on the Septuagint, and the other based on direct translation from the best Hebrew text he could find. Pope Damasus chose the translation based on the Septuagint, so this is what we find in the Vulgate:

"adprehendite disciplinam nequando irascatur Dominus. . . "

It seems to me that both "draksasthe paideias" and "adprehendite disciplinam" could be translated into colloquial English as "learn your lesson." Is this what the Hebrew says? Hardly. Modern editions of the best Hebrew text we have, which dates to 1010 CE, tend to include page notes here (and in many other places), stating that "the meaning of the Hebrew is uncertain." Apparently it was also uncertain for the translator into Greek in 250 BCE, who just threw up his hands and took a shot in the dark, putting in "learn your lesson."

But wait . . . what about the second translation that Jerome offered to Pope Damasus, the one based on a Hebrew text of the time? Fortunately we still have it, and it happens to be included in my edition of the Vulgate (Robertus Weber OSB, 1969 Württemburg, second edition 1975):

"adorate pure ne forte irascatur. . . " (adore purely, lest he should become angry. . .)"

What a difference! Was the translator of the Hebrew text shooting in the dark? As we shall see, it appears that he was not.

Now the Vulgate of the late fourth century CE was not the last Latin translation. In 1945, the Catholic Church published LIBER PSALMORUM CUM CANTICIS BREVIARII ROMANI. If we look up this verse in it, we find:

"praestate obsequium illi, ne irascatur. . . " (pay homage to him, lest he become angry. . . )

Now we are getting somewhere. They have realized that "kiss" (imperative), נַשְּׁקוּ, was meant symbolically: in the ancient world, a kiss was often an act of paying homage and expressing submission. The whole phrase in the Masoretic Text, though, was נַשְּׁקוּ־בַר, and this is where the trouble comes in. In an unpointed Hebrew text, the only kind available before the Masoretes completed their work in the tenth century CE, the second part of the phrase would simply have been written as "בר“ (without vowels). Now the Masoretes mispointed the word as "בַר“ (bar), when it should actually have been "בֹר" (bor). According to my dictionary, this word "bor" means "pureness (of heart)." According to Strong's Concordance, the word (Strong #1252/3) has a constellation of meanings involving "purity," including "purely." Now I did not know this word (I am indebted to Rabbi Tovia Singer for its identification). Apparently the translators of the 1945 Liber Psalmorum did not know it either, because they went down a rabbit hole based on a 1940 article in the journal Biblica which made a tortuous argument based on very little evidence that the Masoretic Text was defective and the reading should actually be "kiss him on the feet." They must have known that their argument was flimsy, because they simply said "pay homage," not mentioning "feet." As we shall see, though, their argument was not without influence.

What is the significance of all this so far? Well, King James' translators apparently jumped to the conclusion that the mispointed word "bar" was the Aramaic word "bar," which means "son." But the Psalms are written in Hebrew, not Aramaic. They are 100% Hebrew poetry, with not a word of Aramaic in them. In the whole Bible, the Aramaic word "bar," meaning "son," only occurs in the books of Ezra and Daniel, which are partly written in Aramaic, and in Proverbs 31:2, where the proverb-collector was quoting his mother, who spoke to him in Aramaic. But it does not occur in the Psalms. At all.

We are not in a position, though, to assert that the translators of the KJV made this misreading intentionally. It is my opinion that they probably did not.

So now let us look at a few post-1611 and post-1945 translations of Psalms 2:12:

RSV (1952): "kiss his feet, lest he be angry, , , "

NASB (1960-1975): "Do homage to the Son, lest He become angry. . . "

NKJV (1980-82): "Kiss the Son, lest He be angry. . . "

NIV (1973-1984): "Kiss the Son, lest he be angry. . . "

NWT (1984): "Kiss the son, that He may not become incensed. . . "

NAB (1970-1991) "bow down in homage, lest God be angry. . . "

TIB (The Inclusive Bible, 2007) "Pay homage to God's Own. . . "

And it is not only in English that the error of the KJV has persisted:

RVR (2017): "Rendid pleitesía al Hijo, para que no se enoje. . . " (Pay homage to the Son, in order that he may not become angry. . . )

VS (1921): "Rendez hommage au Fils, de peur qu'il ne s'irrite. . . " (Pay homage to the Son, lest he should become angered. . . )

If the translators of any of these versions have knowingly and intentionally perpetuated the (convenient) error of the KJV, then shame on them. We are not, however, in a position to assert that this is so.

The post-1611 publications listed above are Christian, though some, such as the RSV, may make an effort to be ecumenical. How do the Jews themselves translate their own Scriptures in this troublesome verse? Let's take a look.

JPS Tanakh (1999) "pay homage in good faith, lest He be angered. . . "

Koren תורה נביאים כתובים (1997) "Worship in purity, lest he be angry. . . "

I submit that both of these are correct. JPS's "in good faith" here means "without ulterior motives or mental reservations," and is certainly the way in which we should approach God. Koren's "Worship in purity" is more literal, and takes us back to Jerome's Hebrew-based translation of the late fourth century CE, the one that Pope Damasus rejected. It is clear from this example that Jerome's Jewish informant was very knowledgeable indeed, being able to extract the correct meaning from an unpointed text. We might have been saved a great deal of trouble, had Damasus accepted his translation.

One takeaway for me in all this is that, in doing my translations of the Psalms, I should give more weight to Jerome's "Iuxta Hebraicum" translation than I previously have, along with JPS and Koren.

A lesson for all of us might be that we should allow a culture to interpret its own scriptures.

Text, except for biblical quotations, Copyright © 2023 by Donald C. Traxler.