That little anecdote shows how well the New Testament saying is known. It is, in fact, proverbial. And yet, it appears only in the Gospel of Matthew (Mt. 7:6). It goes back at least to the Matthew IIb layer, because it is found in Hebrew Matthew. Why did Luke not pick it up? If we look more closely at the saying, we'll see some of the reasons.

"Do not give dogs what is holy." In Rabbi Yeshua's time, the Jews often referred to the Gentiles as "dogs." We see this, for example, in the story of the Syro-Phoenician Woman (Mt. 15:21-28), where we also see that the Gentiles understood this derogatory term as referring to them. So Luke, whose Gospel was written for the Gentiles, would obviously not have included it.

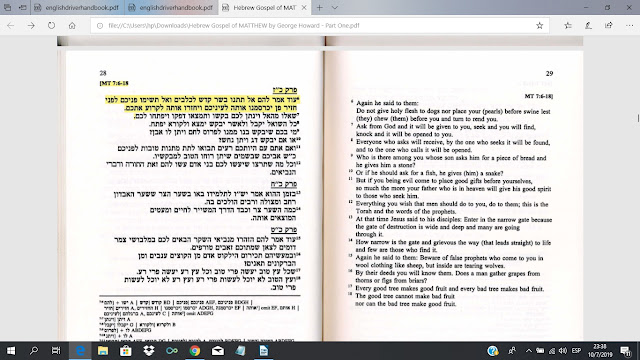

But there is more to see. Instead of "that which is holy," Hebrew Matthew has "holy flesh." This is a "translation variant." {See Howard, op. cit., p. 226.] The Hebrew phrase בשר קדש (holy flesh) looks very similar to אשר קדש (that which is holy). But the similarity only exists in Hebrew, not in Greek. So the person translating Matthew from Hebrew to Greek took it to be "that which" instead of "flesh." This is good evidence for the "Semitic Substratum" in Matthew. Now, there is a principle in textual criticism by which the "more difficult" reading is probably the correct one. Certainly "flesh," being much more specific than "that which," is the more difficult reading. But what could it mean? To me, it sounds like a prohibition of mixed marriage. The reading in Hebrew Matthew is probably the correct one, while canonical, Greek Matthew has preserved a translation error.

As to the rest of the saying, "Do not throw your pearls before swine," the meaning seems clear to me. It is a warning against proselytizing. Hebrew Matthew says, "Do not give holy flesh to dogs, nor place your pearls before swine, lest (they) chew (them) and turn to rend you." Isn't this exactly what happened? But the whole saying would have been offensive to Luke's Gentile audience.

So we know why Luke didn't pick up this saying. That could also explain its absence in Mark, who was probably writing for the Romans But why, then did he omit essentially all of the material that we, without any real proof, call "Q?" This is still an unresolved question in my mind, but the most likely answer is that he never saw it.

I am struck by the very high quality of the "Q" content, especially in the "Sermon on the Mount/Plain." Ethically, it is defining for Christianity. No writer of a Gospel could afford to leave this material out,unless they were unaware of it. The "Q" material is full of catchwords, a feature of the oral transmission stage, so it probably came directly from the orally-transmitted traditions of the earliest "Christians," who were also Jews. As Papias and other ancient writers tell us, Matthew collected these sayings, or "logia," and wrote them down in Hebrew. This collecting would have taken some time, and Mark may have benefited from an early version of Matthew (which I call Matthew I), still lacking most of this logia material. This, it seems to me, is the most likely answer. Mark, who needed to explain Jewish customs to his audience, as Matthew did not, may have himself been a Gentile. Robert Lisle Lindsey, who translated the Gospel of Mark into Hebrew, said that it was the most difficult of all the Greek Gospels to so translate. He even suggested that it may have originally been written in Latin.

The writers of the other Synoptic Gospels did not need Mark. Only three percent of Mark's content is unique to him. The easiest answer is that he used an early version of the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew I), still lacking much of the most important material. By the time of the formation of the New Testament Canon, Mark's product was obsolete. Mark's gospel was almost not admitted into the Canon, but finally was accepted because of his association with Peter, an eyewitness. All I can say at this time is that the case for "Markan Priority" is far from convincing.

(to be continued)

Text © 2019 by Donald C. Traxler.